I finally pinned down Matt Tilton, Seattle’s best blacksmith, to do an interview with me. After my first request via text, way back in December, it took seeing him on a group camping trip to make this happen. After a super-expert marshmallow roasting session (and honestly, who better to roast marshmallows with than someone who puts things into hot fire for a living?!), he finally agreed to do an interview with me.

PS- he didn’t get my first text, and was more than happy to do the interview once I asked in person. 🙂

Lindsey Runyon: I love that you are a blacksmith, it sounds like such an old fashioned profession. For those of us who may not fully understand, how is a blacksmith relevant in today’s society?

Matt Tilton: Pretty much the same way they’ve always been relevant. Blacksmithing was called the “king of trades” because basically, it’s needed for all trades; it’s the foundation set of skills for all industry. It’s used still in everything from making washers for a battleship all the way to hooks and brackets at your house.

LR: It’s totally relevant – anything to do with metal, right?

MT: Pretty much.

LR: What is your number one rule of blacksmithing?

MT: Safety third! ……Or… Get it hot, hit it hard.

LR: “Get it hot, hit it hard.” Love it.

LR: What percentage of the time, lifetime career percentage, do you sleep overnight in your workshop?

MT: Wow. I don’t know percentage, but I would say that there was…Ok, I’m not going to do the math, but let’s say 25 nights a year.

LR: 25 nights a year. Respectable number.

LR: What would be your ideal project or ideal client?

MT: It’s one I’ve already done once, which is public art. Changing the landscape of the city is important to me. And artistic freedom. That is kind of always the goal.

LR: Do you think that public projects give you that artistic freedom?

MT: So far they have. Sometimes there are committees that can get in the way. On my first public art project I was able to do whatever I wanted, but that was a public/private collaboration kind of project. Through the City of Seattle, there’s also a program called “Small and Simple” which are grant projects for anything up to $25,000. Those you definitely have to jump through a lot more hoops, but it can be anything from a sculpture to actually utilitarian goods. Right now we’re applying for a grant for historical signage and lighting for Post Alley.

LR: Oh, cool. So do you feel like you’re more of an artist or more of a craftsman/tradesman? Because when you say you want artistic freedom that makes me think you’re more of an artist.

MT: Well, I guess for what I want to be doing with the public art, yes, I’m more of an artist, but I also have a furniture line and I make a lot of utilitarian goods. There I have complete freedom because I designed it in the first place.

LR: You are the boss.

LR: What is the most dangerous thing you have ever done?

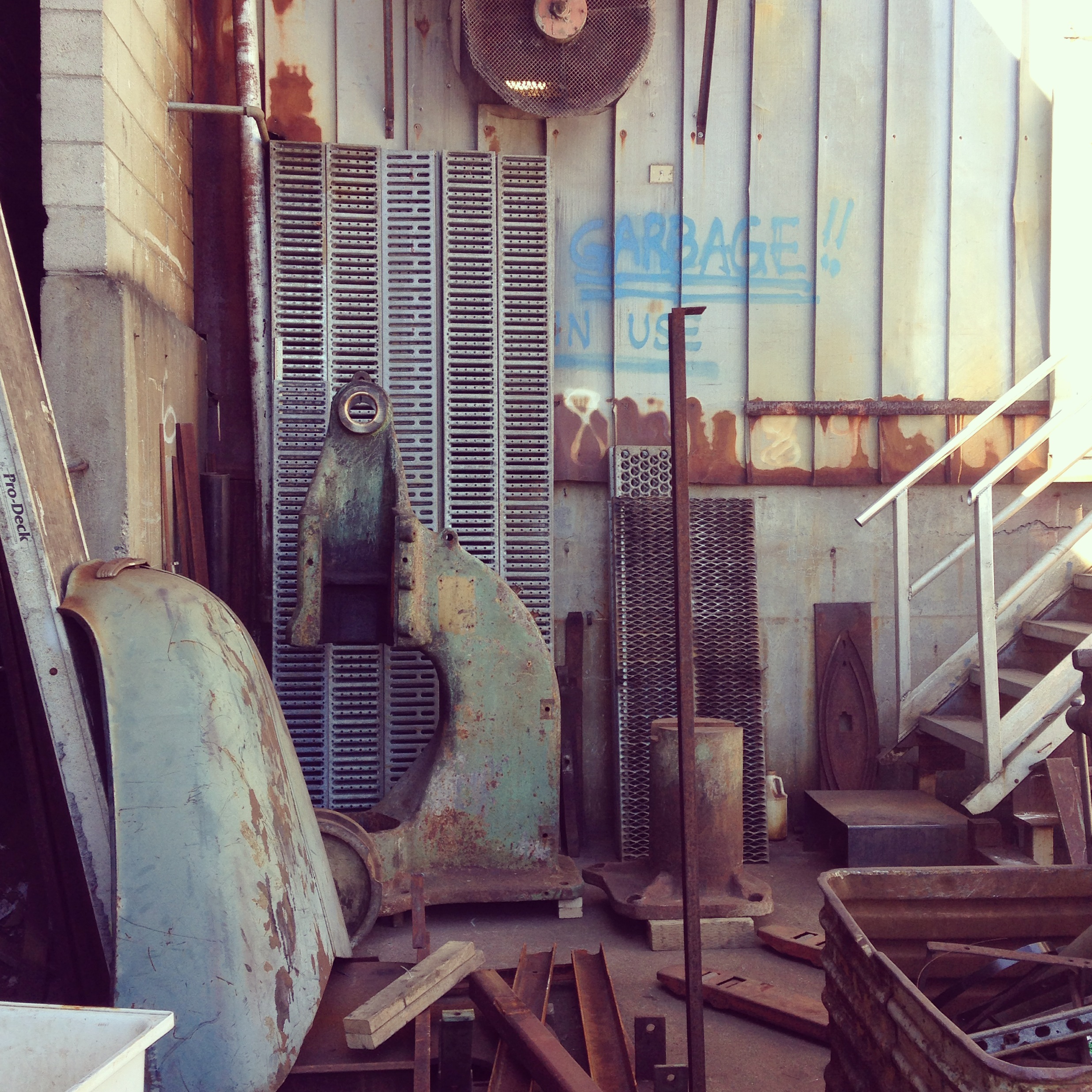

MT: Moving my shop, haha

LR: Really? Why?

MT: It’s just a lot of forklift work and, you know, large machines swinging overhead…Yeah, the biggest machine weighs 4800 lbs.

LR: Phwew! OK, that’s sounds pretty dangerous.

LR: How are you eco-friendly with what you do?

MT: The nice thing about blacksmithing is when you’re doing ironwork, is all the material is 100% recyclable. And, the way I look at conservation and goods, the things we make don’t go away. When I make a, say a $20,000 gate, I know that it’s going to be around for hundreds of years. So longevity plays a big part…I originally did ceramics and felt that the longevity wasn’t there in my work. So, when I moved over to ironwork I felt a lot more eco-friendly.

LR: That’s great, and that’s actually a perfect segue into my next question of how did you get into blacksmithing? Is it something you wanted to do since you were a kid, or…?

MT: I actually, found this out when I became a blacksmith – my mother told me that I had been hanging out at the town blacksmith’s garage on our dead end street in a small town. And, I just remember that there was fire and sparks but I don’t remember anything about what he was doing. And it turns out I was just hanging out at his little shop at home after he retired.

LR: Oh. You were meant to be. It was meant to be.

MT: Yeah, I went to school originally for mechanical design and engineering and then went into ceramics at art school and I was a hand-builder in ceramics. That continues to the way I work steel. It is still kind of a process of squishing out the shape, kind of the way I was working with ceramics. So I feel like I’m still doing kind of the same work I’ve been doing since all the way back in to college—manipulating shapes.

LR: Were you an apprentice or how did you learn how to do blacksmithing when you went to school for ceramics?

MT: Well, when I was in ceramics school I also took some metal shop classes at MassArt. I moved here in 1990 and walked into a blacksmith shop in Pioneer Square. It just completely thrilled me, and I quit being a kitchen manager and started an apprenticeship for three years. Making an astounding $5.25 an hour.

LR: Haha, nice.

MT: And, the early 90’s in Seattle was a really growing community and immediately got commissioned to do some public work, and just kept going.

LR: Approximately how much whiskey is consumed at a blacksmithing conference?

MT: ……………….Let’s just call it a barrel.

LR: A barrel? I don’t even know how much that is. A lot I’m sure, haha.

LR: Does the phrase, ‘Strike while the iron’s hot’ have special meaning for you?

MT: Yeah, well, it’s the only way!

LR: Get it hot, hit it hard!

MT: Get it hot, hit it hard!

LR: OK, great, well that concludes our interview and I have to say you were the best marshmallow roasting coach I’ve ever had! Thank you.

MT: Thank you!